Written in partnership with Pedro Portela, Hive Mind Institute

The Plight of the Social Activist

Many social activists can relate to the following scenario. They sign up for an intensive training in a beautiful nearby region, with the intention of networking with fellow activists and learning about social change and innovation. The timing is perfect – they feel like they’ve been working alone for years and are struggling to see the impact of their efforts. They sense that what they’ve been doing has a significant impact on the people they touch, but at the same time they feel like a mere drop in the ocean.

They keep seeing the same patterns of behavior and destruction around them, regardless of the enormous amount of energy and creativity they’ve put into their work. The problem just seems too big and intractable.

They think they’ve found the perfect training – one in which they’ll learn about systems thinking and how the tiny efforts of a small group of committed individuals can add up to create massive, exponential change. Linking is a central idea, and the concepts of ‘network’ and ‘network weaving’ are thrown at them throughout the training. They learn about complex systems, emergence, tipping points, and the viral spread of ideas, all while participating in discussions and creative dialogue sessions where a deeper understanding of their peers’ interests and struggles is achieved. They partake in fascinating group dynamics and games meant to challenge certain mental models and an unsustainable amount of post-it notes are consumed in an effort to define goals. As a group, they go through the usual stages of development: forming, storming, norming, performing and adjourning before waving goodbye to their colleagues and facilitators.

In the time following the training, the group stays in touch – those who live close to each other organize meetings and casual get-togethers, while others join via Zoom. Some of the participants even go as far as successfully planning activities together. However, others begin opting out as the pace of life returns and the effect of their time together starts wearing off. It’s hard to meet given everyone’s schedules and other issues arise such as internet connectivity and disagreements on the preferred communication platform.

It’s not long before everyone reverts to the same routine of hunting for the next funding opportunity in order to put food on their tables. The training becomes a fond memory for the activist. They keep in touch with the new friends they’ve made, but the vision of a strong coalition to bring about big systematic change now seems very distant. New relationships were formed and a network was weaved, but they feel that they’re back where they started, focusing on their own work and wondering whether their small efforts will indeed produce any meaningful change amidst the powerful status-quo.

Disrupting the Pattern

If you can relate to this story, you’re not alone. Many activists, change makers, social innovators and civil society leaders have gone through this experience. It is a pattern.

What is the blind spot of social networks? The governance in the networks that fuel social change movements. Despite the recent interest in the shift towards networked strategies for social change, there is still a lot to be explored concerning the questions surrounding decision making and the establishment of network policies together with its collective mission.

A deep and structured conversation about network governance is required and needs to be included in the design process of network initiation. It is an integral part of the responsibility of NGOs who convene networks and should be held and carried out by the funder and donor community worldwide.

Systems Change Networks and Their Governance

In one way or another, most social movements are a form of challenge to established powers. That power can take the form of an oppressive regime, an unfair economic system, or corrupt systemic status quo. The latter is the most difficult to tackle since it does not have a simple hub and spoke structure that can be understood and dismantled piece by piece. Examples of systemic status quo are racism, environmental violence, or protracted civil conflict.

This article addresses the struggles related to shifting systems, particularly the ones that have no linchpin or clear leverage points: no regime to topple, no significant companies to sue, and no peace treaty to negotiate. There may be no clear endgame or road towards it and no clear definition of success or failure, other than a sensible change of the current status quo.

These are the most difficult struggles to pursue for social movements and the networks fueling them as they entail a bitter provocation to the network members. They may be asking themselves:

“Is the way we self-organize to change the status quo not a mere reflection of the status quo itself? Aren’t we simply replicating old patterns of working and “fighting” that contain within themselves the seeds that created the current status quo in the first place?”

If taken in earnest, this provocation gives rise to a tension that many social change movements face and fail to overcome. The movement needs to become agile and organized enough to plan and coordinate many different small scale actions across the spectrum of the complex field they are operating in. A network strategy is said to be adopted: instead of a few large scale actions coordinated by a central committee, many diverse and synchronized small scale initiatives are planned. These initiatives are not organized or mandated centrally. Still, they are attuned to a set of shared, high level, mission statements and principles, leaving the details of their execution to the local change agents.

Yet, this mere synchronization requires a form of governance and hierarchy. There are decisions to be made, actions to be taken, people to speak to, and money to spend. But the typical form of governance where a leader is elected by majority vote leads to a network topology that is not suitable for dealing with complex problems. This approach tends to degenerate from the concentration of power and authority held by a few individuals in the network, which is exactly what social movements wanted to avoid in the first place.

The Square and The Tower

In the 2018 book The Square and the Tower: Networks, Hierarchies and the Struggle for Global Power, author Niall Ferguson takes the reader through history’s defining moments by putting in perspective the role that individuals and social networks played in them. The book uses the metaphors of “the square” to symbolize the place where informal, loosely structured social networks end up convening, and “the tower” to represent the formal top-down hierarchical power. The author challenges the somewhat romantic idea that networks or movements spun with the help of modern communications technologies have the ability to replace traditional systems of governance. Although Ferguson’s analysis sounds about right, it is missing the contribution of another geometric shape: the circle.

Governance is a heavily loaded word. It brings about associations with concepts such as government, bureaucracy and power over people. Yet, every system, be it natural, artificial, social, biological or mechanical, needs a form of self-regulation. We call this process of self-regulation “governance”. It is a process by which the system senses the outside environment and adapts its actions in order to fulfill its purpose accordingly.

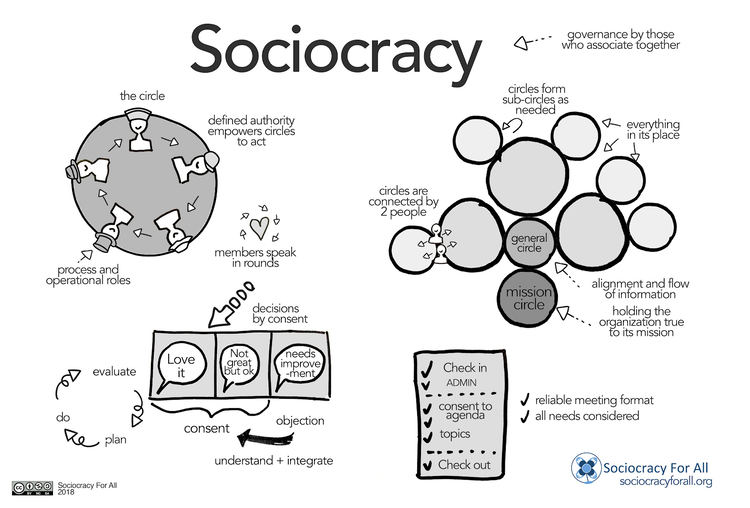

How to achieve this process of self-regulation while balancing the tension between collective purpose and individual freedom is the value proposition of Sociocracy. Sociocracy has been around since the mid-XIX Century and has the circle as its building block for decisions and sense-making. It’s a system of governance designed around the values of transparency and equivalence but with inspiration from cybernetics (the science of how systems use and exchange information to self-regulate).

In Sociocracy, decision making takes place in a Circle of Shared Power rather than in the Square of the Loudest Voice, or the Tower of Power-Over. It is also aimed at optimizing resource efficiency where decisions are made by consent instead of consensus which usually results in endless debates among network members. By consenting to a decision you are not necessarily agreeing with it, but you’re not objecting to it either; and this, as subtle as it may sound, makes a world of a difference.

Another aspect of Sociocracy which makes it a perfect system of governance for systems change networks, is the way it balances agility with accountability. Working in a complex system requires agility, which involves the ability to pivot on a moment’s notice based on real-time information and significant changes in the local environment. This is incompatible with rigid, heavily bureaucratic and procedural governance systems. But procedures and bureaucracies were invented for a reason. They provide for traceability and accountability. Sociocracy solves this tension by letting power flow to the node of the network which is most impacted and closest to the action. In this case, the power flows to the local change agents acting within a very well defined domain. Those who are most affected by a decision are empowered to make the decision, while at the same time are accountable to the “aim” (domain of action) of their circle members, which is also in support of the aim of the organization.

Transparency, communication and accountability across the organization are accomplished through an interlinking circle structure.

Each circle is connected to the rest of the organization through specific roles that interface with a “general circle” which is then connected to a “mission circle”. In this way, information and feedback flow through the system at all levels of the organization. This forms an organizational structure resembling a set of nested circles that provides a flexible hierarchy where decisions are made at the most local level possible, while maintaining the integrity and alignment of the entire system.

Empowered Networks

The power of isolated local change agents is bounded by their radius of reach, their community, their field, and their organization. When embedded in a systems change network, their power can be leveraged by clever usage of the network effects. Nevertheless, this can only happen if there’s a governance system in place that invites their voices to be heard, incorporates feedback loops, and is well structured yet malleable enough to allow for agile adaptation to the changing, dynamic environment.

Such a system is not straightforward and one shouldn’t expect groups or nascent networks to find a solution for the critical governance tension quickly. Sociocracy is just one example of a system of governance that is more aligned with the requirements of systems change networks.

In addition to fostering connectivity between local change agents and nurturing social spaces for cross-pollination of ideas, funders and donors are missing the opportunity to invest in setting up a governance system which empowers the network to thrive.

This governance system does not need to be perfect. Its effectiveness comes from an agile approach. Look for what solves the immediate problem while supporting your network values and is “good enough for now, safe enough to try” (a principle used in Sociocracy and Agile Methodology).

The year 2020 will be remembered in the history books for many disruptive events. It will also be looked back upon as the year that our civilization’s complexity and interconnectivity became revealed in unprecedented ways. In our role as supporters of social change movements, we are being called to rise to the occasion and earnestly address the blind spot around group governance and power so that we can effectively respond in these volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous times.

About the Authors:

Bernadette Wesley is an Organizational Development Consultant and Sociocracy Trainer

Pedro Portela is an independent consultant in the areas of Systems and Complexity Thinking

Republished with permission of the author.

Community Discussion

Click here to start the discussion of this article.